The maritime world wants – and needs – to get greener. This is more than an outworking of the Paris Climate Accord – it’s also the stated aspiration of many shipping companies, shipyard operators and skippers. But what waters have to be navigated to get there?

“The key enabler for greener shipping is the fuel,” emphasizes Dr. Daniel Chatterjee, Director of Technology Management & Regulatory Affairs at Rolls-Royce Power Systems. E-fuels such as e-hydrogen, e-methane, e-methanol, e-diesel or e-ammonia, which are produced from renewable energy sources and subsequently refined, can be converted into propulsion power in ways that are climate-neutral.

But as clear-cut as this may sound, it is actually anything but, because many questions are still to be answered:

- Which e-fuels are set to win the race?

- When will these be available in sufficient quantity?

- And what propulsion technologies are needed to make use of them?

One thing we do know is that we’re not going to see any one-size-fits-all fuel, but rather a coexistence of various different fuels and propulsion technologies. Hydrogen, for example, which is converted into energy in a fuel cell or a combustion engine, is just as much on the cards as are e-methanol, e-methane, e-diesel or e-ammonia.

Battery or e-fuel?

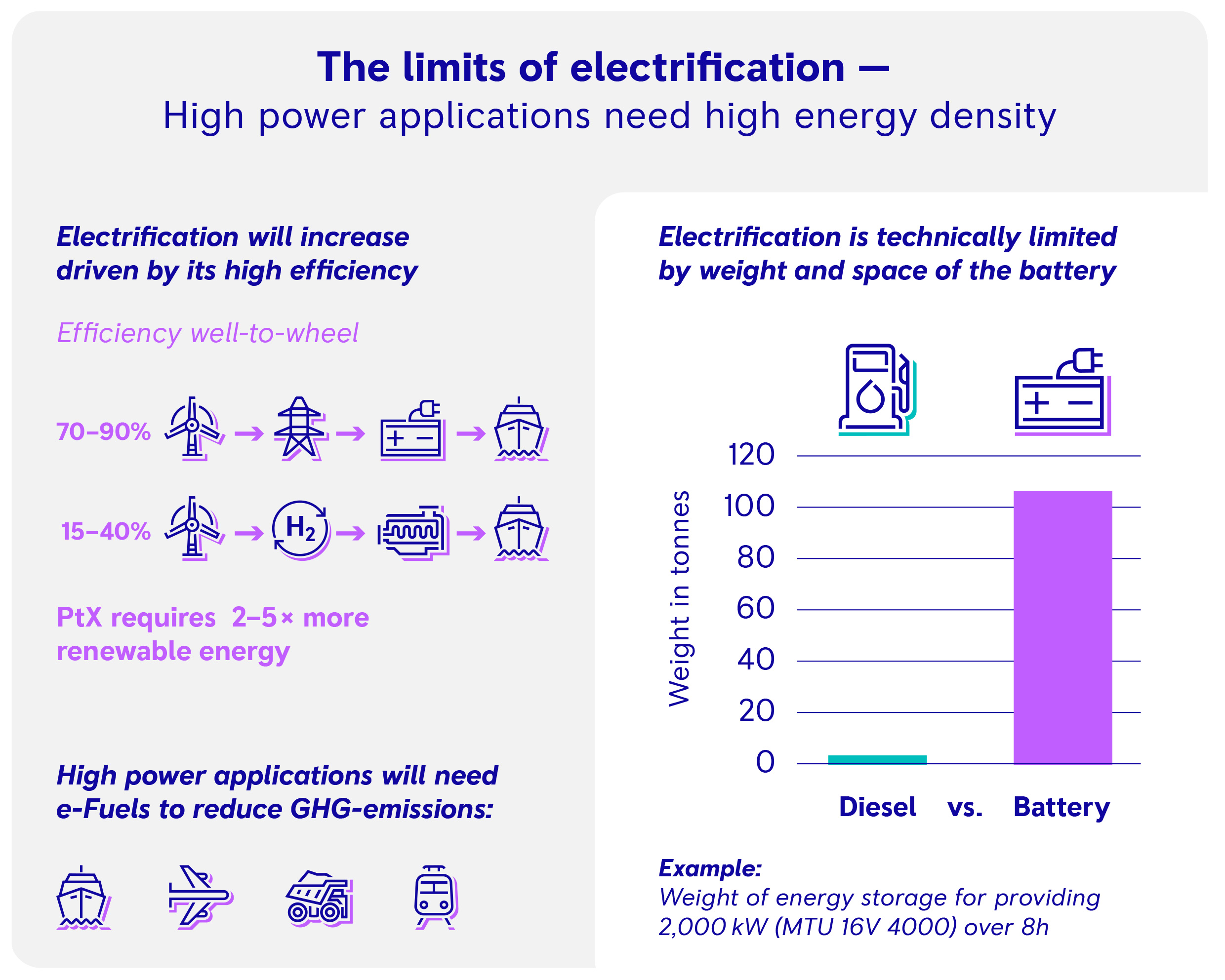

One question rears its head right at the outset: Why not use electricity directly, storing it in batteries and using it to power electric motors? At first glance, this seems more efficient, as no energy is lost in converting electricity to e-fuel. But alas, the energy density of a battery is much lower than that of e-fuels. To run, say, a Series 4000 V16 engine for eight hours at an output of 2,000 kW would take over 100 metric tons of batteries.

Power-to-X enables global energy trading

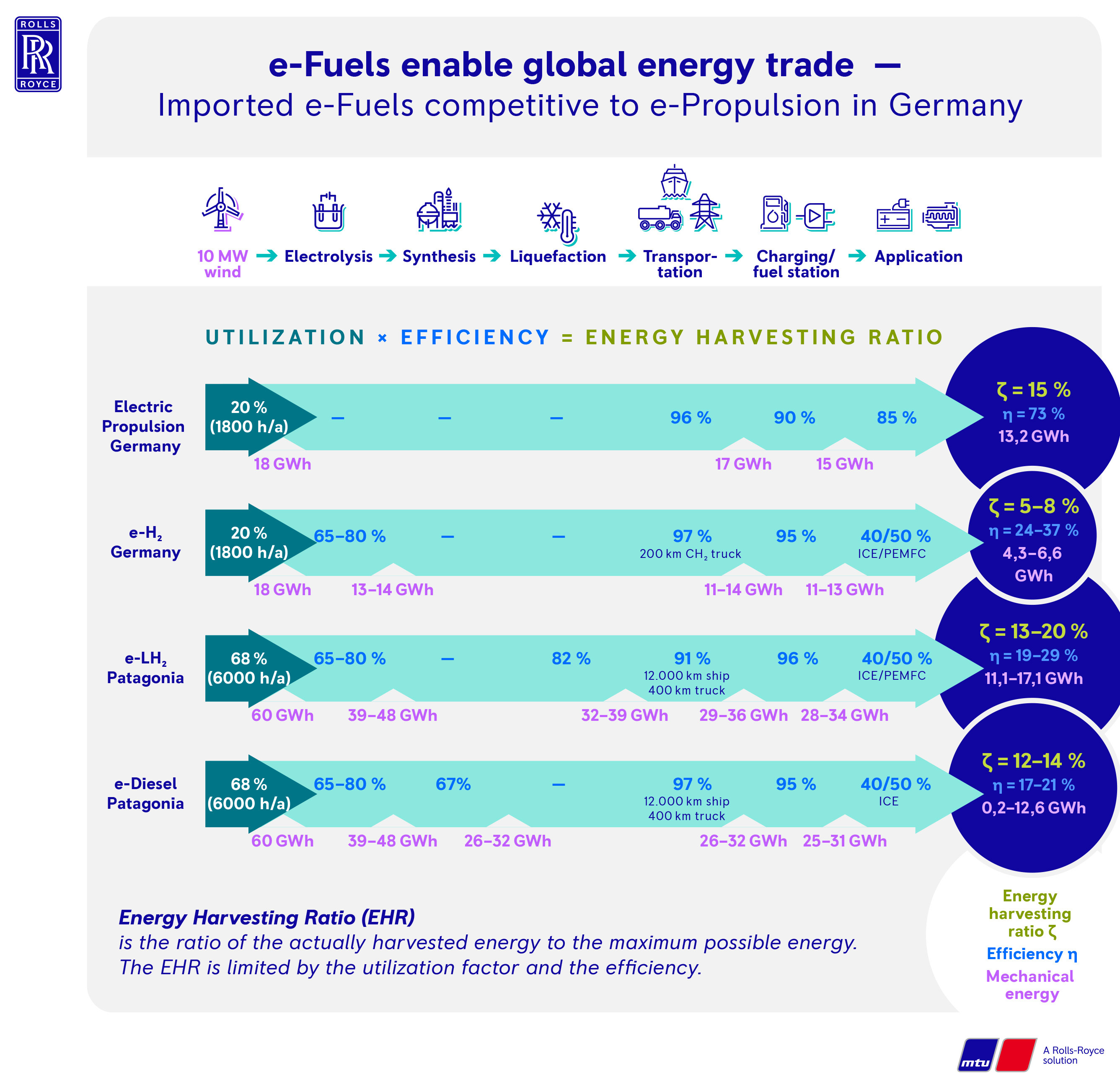

But the energy density of e-fuels is not the only argument for using them. They also enable energy to be traded globally. In Patagonia or the Sahara, for example, there is huge potential for generating power from renewable sources. The utilization rate of a wind turbine in Patagonia is three to four times that in Germany. However, the electricity generated there cannot be transported to Germany, where it is needed. But if the electricity is converted into fuel in Patagonia using a Power-to-X process, such fuel can be transported with relative ease. Although much energy is lost during conversion and transportation, more energy is available at the end of the process than would have been generated directly in Germany. Ultimately, the world’s total energy needs will only be met by exploiting potential such as this.

The search for the right Power-to-X fuel

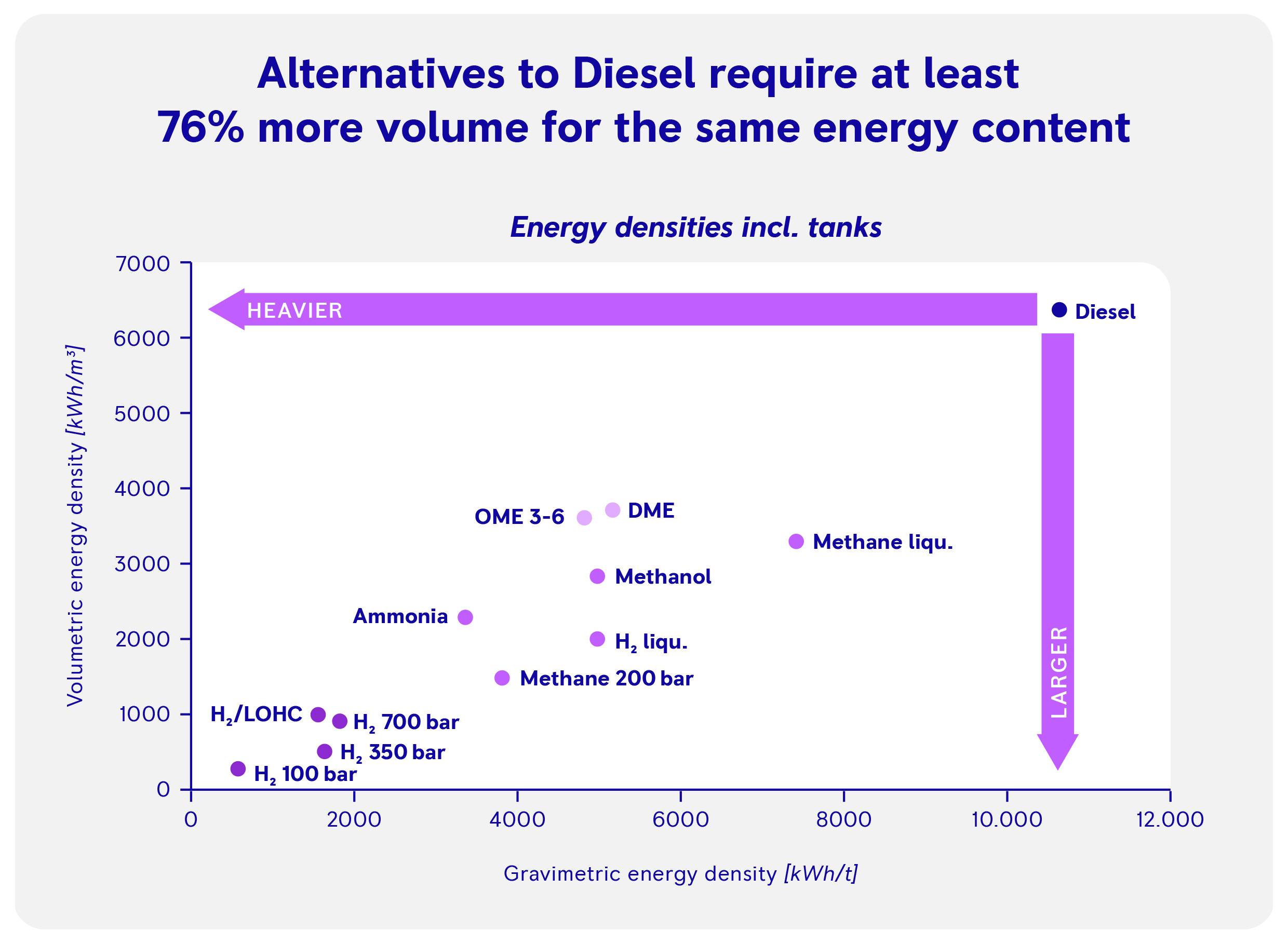

In various studies, a team of Rolls-Royce experts is currently working with customers and industry partners to examine the entire system – from fuel infrastructure, the cost of creating it, and vessel range to the propulsion system and building it into the vessel. What all e-fuels have in common is that they have a much lower energy density than conventional diesel. This means that the weight and space requirement of fuel tanks increase in every case – but not to the same extent for every type.

Hydrogen for ferries and tugboats

As a result, ferries or tugboats operating on defined, short routes are more likely to use hydrogen as a fuel because they can refuel frequently and can reckon on this fuel being available at their port of call. Experts at Rolls-Royce expect that as early as 2035 over half of all the world’s ferries and tugs will no longer be diesel-powered.

Internal combustion engines will continue to be used in yachts

For yachts, too, the trend is moving away from conventional diesel combustion engines, with many owners already using hybrid systems combining diesel and electric engines with battery systems. Fuel cells will be commercially available in 2030 and will be able to replace diesel generators for power generation tasks. Used as part of hybrid electric powertrains, they will also provide part of the propulsion required. However, the internal combustion engine is not set to disappear from yachts. This is because range is a major consideration for many yachts, and they are often cruising in exotic locations where one cannot count on new-style fuels such as hydrogen or methanol being available. This is where diesel remains an important option – in the form of carbon-neutral e-diesel. It will continue to be available at most ports and has a much better energy density than hydrogen. And e-diesel can also be used in existing engines.

E-ammonia is also an attractive option as a marine fuel, although for safety reasons Rolls-Royce experts do not currently foresee it being used in coastal shipping, i.e. in ferries, tugs or yachts.

“We’ll need to commit to a certain path in three to five years’ time.”

“Our experts are still investigating the entire eco-system with the aim of pinpointing the best solution,” said Daniel Chatterjee. But he says one thing’s for sure: “We’ll need to commit to a certain path in three to five years’ time at the latest in order to achieve our overriding goal of making shipping climate-neutral by 2050.”

Yet this goal still seems so far away. However, a simple calculation shows that preparations for this must begin now: Ships have service lives of anywhere up to 40 years. If the entire shipping industry is to be climate-neutral in 2050, the vessels in service then must be planned today. Any vessel entering service in 2030 must have climate-neutral propulsion. If this is to be built in 2027 – assuming a three-year construction period – the decision on the propulsion system, and thus the fuel, will have to be made in the years leading up to this.

Political support called for

Rolls-Royce studies show that the huge demand for e-fuels – 20,000 TWh of energy per year, the equivalent of around two trillion liters – cannot be met before 2030. The technology is certainly available, but not yet on an industrial scale. “Advancing this and creating the framework for these fuels to find a market need the support of political decision-makers,” urges Chatterjee.

He is looking forward to the many discussions with customers and industry partners on the appropriate choice of fuels and propulsion systems. “We’re at the beginning of a major maritime transformation. Being part of that is a fascinating task,” he concluded.