The maritime industry is experiencing a phase of rapid technological development. The shift from paper charts to continuous digital connectivity is resulting in a myriad of operational changes. With it, comes growing environmental concerns and ever-stricter safety standards. Yet, accidents still happen and people get hurt. This article examines the data and considers issues spanning the sector, looking at how regulation is shifting to address it and how technology can play a role in risk mitigation

Current safety environment

Recent years have seen fluctuating safety performance across the workboat world. Each subgroup faces its own challenges leading to incidents involving injury, equipment damage, and pollution.

In the crew transfer sector, huge investments have been made in the last 20 years but still, overlooked hazards and poor risk management are seen in crews treating safety as a tick-box exercise. The Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) reports indicate that incidents typically arise not from technical failures, but from poor decisions due to insufficient training or lack of supervision.

MAIB tugboat investigations repeatedly highlight the need for better training, clearer communication, robust procedures and a stronger safety culture. These issues mirror those found in crew transfer vessel incidents, showing that organisational and human factors are key to preventing accidents.

The fishing industry remains the worst performing sector for fatalities despite safety campaigns and regulatory efforts.

However, Rigid Inflatable Boat (RIB) operations have a disproportionately high rate of serious injuries, particularly spinal, compared to any other small vessel sectors. These incidents are almost entirely concentrated in the commercial leisure market. Persistent safety issues and repeated incidents yield the same injuries with a lack of regulatory improvements. Over the past 25 years, more than 50 incidents have been documented, with 17 cases involving spinal injuries. Two further spinal injuries have been reported in 2025 to date.

Trends in safety failures

Analysis of incident data and industry feedback reveals several recurring issues that undermine safety. Human error is the greatest contributor to accidents. The industry often fails to meet safety standards, not because of a lack of knowledge, but due to cognitive limitations, habits, and pressures. Operators are prone to complacency, especially in familiar environments, and may underestimate risks encountered without consequence in the past. Even with well-written procedures in place, human nature tends to favour production over caution.

Mechanical failures are the next significant contributor to maritime incidents, often stemming from aging vessels, maintenance neglect, and non-standard modifications. Some failures are due to hidden defects or gradual wear that escapes detection until a critical breakdown occurs.

Regulation, culture, and industry response

Workboat Code Edition 3 came into force on 13 December 2023, a major regulatory overhaul for the UK’s workboat sector. Designed to modernise safety standards and respond to emerging technologies, the code introduced stricter requirements for vessel construction, maintenance, and crew competence.

However, its arrival was met with widespread discontent. At an industry event in Southampton, industry frustration was made publicly clear.

The backlash wasn’t just about cost or complexity; it was about human capacity. While the Code targets mechanical and procedural risks, it does so by layering on more checks, documentation, and compliance tasks. This approach assumes that more rules equal more safety. But it may do the opposite. By increasing the cognitive and administrative load on crews, the code risks overwhelming the very people it aims to protect. When safety becomes a checklist rather than a mindset, the consequences are well known.

Regulation must go beyond technical compliance. It must engage with the human element – how people behave under pressure, how they make decisions, and how they respond to risk in dynamic environments.

Examining the commercial leisure RIB sector reveals what’s being done about the worst performing statistics. These operators face a growing burden of overlapping codes: Workboat Code 3, MGN 436 Effect of impacts and shocks on small vessels, the imminent Sport or Pleasure Code, and MAIB Safety bulletins. For many, especially those without dedicated compliance staff, the sheer volume can feel overwhelming.

A paradox exists in Work Boat Code 3. There is a strong track record of injuries linked to whole-body vibration and high-impact shocks. These factors have been shown to cause serious nerve damage to RIB occupants. The code’s first requirement for impact or hull stress monitoring devices is found only in Annex 2 and applies to remotely operated, uncrewed vessels. A recent MAIB report issued after a RIB passenger was paralysed from the waist down stated in its recommendations to “install to all company-owned rigid inflatable boats sensors that provide real-time measurement of the forces experienced in the boat’s forward section to better enable the person at the helm to protect passengers and crew against the effects of vibrations and shocks.”

Historically, monitoring devices have been advised for larger ships to ensure hull integrity. Now, the focus has shifted to uncrewed vessels, replacing the “feel” that operators once had when physically present. Yet, the opportunity to gather important data and drive meaningful change in the commercial leisure sector has been missed entirely.

Michael Cowlam, Director of Seacroft Marine, with 25 years of experience in high-speed craft for civilian and commercial search and rescue, explains: “For most of my career in coastal and offshore search and rescue the issues with whole body shock and vibration have been well known and widely discussed at industry and corporate level but there has been little in the way of technology implemented in day-to-day operations in the sectors I have been exposed to. Training, awareness, experience and good judgement is invaluable but finding the balance of risk versus reward is often down to the attitude towards risk adversity or tolerance of the individual in command or at the controls.”

This reinforces the safety culture ethos, something that cannot be mandated by code or developed in a laboratory.

Technological advancements have been introduced across the maritime sector to address persistent operational challenges. Electronic chart systems will eventually replace paper charts entirely. Remote engine monitoring is turning planned maintenance into predictive maintenance and Starlink has launched connectivity to new heights, making uncrewed operations exponentially more achievable.

Can technology help?

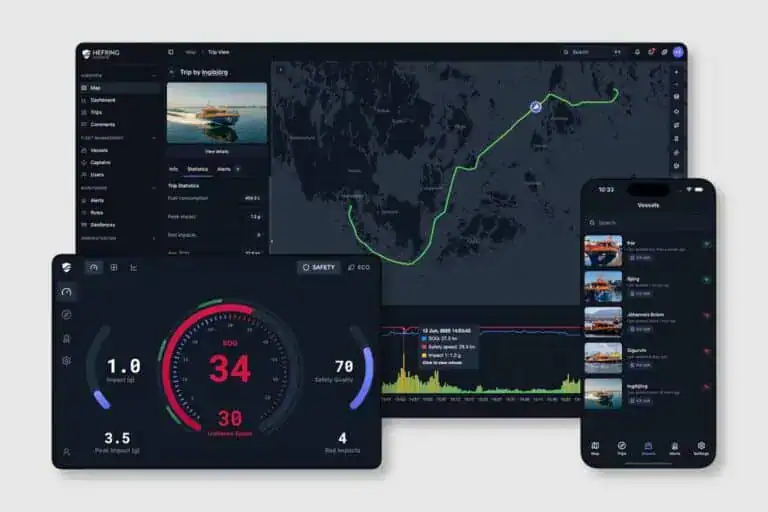

The challenge remains complex. The Intelligent Marine Assistance System from Hefring Marine offers a solution that targets several identified issues, most importantly mitigation of the risk of human error. IMAS provides real-time predictive analytics and safety recommendations, helping operators make informed decisions thereby reducing the likelihood of high impact events leading to injury or mechanical failure. IMAS ingests data from onboard sensors, including vessel motion and hull impact measurements and merges it with external sources such as weather forecasts and surf reports. The AI models continually process data and give the operator speed recommendations and an indication of risk. Speed adjustments directly affect fuel consumption and carbon emissions; impact reductions protect both people and payload.

By providing individuals with their own data insights, the impact of their actions is evidenced and understood instantaneously. This fundamentally shifts the dynamic from passive compliance to active engagement. When operators are equipped with meaningful insights about the conditions they encounter and their responses, they become participants in their own safety, rather than mere subjects of regulation. Once predictive systems are validated and personnel see the value as an active assistant at sea, a positive shift in the workforce is inevitable. Hefring Marine has nearly a million nautical miles of experience from vessels worldwide, each facing unique conditions that are recorded and used to refine the machine learning models.

In the uncrewed surface vessel sector, IMAS provides direct compliance benefits. Fuel efficiency benefits and motion/impact reporting give remote operators a digital onboard presence. Knowing exactly how hard drivetrains and payload management racks are being impacted will have a positive effect on maintenance requirements and help reduce downtime. As USVs move into energy infrastructure offshore for survey and ROV deployment activities, real-time wave height and predictive analysis will enable operators to maximise weather windows. Knowing what is happening at the vessel will boost confidence and operational productivity. Through performance review and open data access, operators can fine-tune their operations.

Organisations like the Norwegian Sea Rescue Society have embraced the opportunity to gather operational data insights. While simple strain gauges can be found for pennies, they lack meaningful insight other than telling operators how large the force was that broke the boat.

Ultimately, the challenge remains for all stakeholders to take action to improve safety outcomes and address persistent issues facing underperforming areas. While technology like IMAS offers genuine potential, it will only work if the integration process is conducted thoughtfully and collectively within the business. The statistics won’t change themselves, so it’s up to the industry to evaluate how technology can be applied to support operations, knowing its limitations, through regulatory change, operational execution and most importantly, the human element.

By Simon Adams, Founder and Director of The USV Group, a marine technology consultancy specialising in uncrewed surface vessels and maritime innovation